My Journey with Instructional Coaching

Getting the most out of instructional coaching.

In the Fall of 2015, I was in my 7th grade math and science classroom during my planning period when my principal came in and asked why I seemed to be down lately. I was in my 6th year teaching that course; and like some teachers who find themselves “stuck” after years of teaching the same subject/grade level, I suppose I was wanting more with my career and profession.

For the previous five years, I had been a teacher-leader collaborating on transitioning the school to standards based grading and reporting (SBG), and my principal desired to have more support for her teachers during this process. This provided an opening for me to be a Learning Coach for the following year focusing on individual instructional coaching, curriculum coordination, and continued work with SBG.

However, while knowledgeable about standards, curriculum, instruction, and assessment, I had two problems:

I had no training on being an instructional coach.

I had very little experience in elementary classes and other disciplines other than math, science, and social studies.

I once had a kindergarten teacher bluntly state, “Eric, I have no idea how you could possibly help me.” Taken aback, I tried (and failed) to explain how I could support her, but she saw right through me in my inexperience. Fourteen years of teaching, training with international experts in disciplines, and a doctorate in curriculum and instruction could not provide with necessary knowledge and skills needed to perform one of the basic duties of being an instructional coach.

Luckily for me, I was able to receive the training I needed to be successful. I joined two other coaches the school had recently employed and together we joined our district training with instructional coaching consultant Steve Barkley. As a cohort, we met with Steve several times throughout the course of the year developing our understanding of student centered coaching, communication models, coaching cycles, delivering feedback, and asking the right questions. His delivery, examples, visuals, and methods for instructional coaching were so clear, practical, and relevant, I felt much more confident working with teachers as a learning coach.

At the same time, I began studying and familiarizing myself with the academic standards other other disciplines. I chatted with foreign language teachers about the ACTFL standards, music and art teachers about the NCAS, PE teachers about the SHAPE standards, teachers from the UK regarding the National Curriculum, and early childhood teachers about Reggio Emilia. To me, it was important to be able to ground myself in the standards as a way to open conversations with teachers at all grade levels. In any conversation, I was not the expert in their content and pretending to be would not help with building a relationship of trust. Instead, my constant refrain was “What do the standards say?” and then rely on my training with Steve Barkley to ask the right questions to determine what the teacher really wanted out of any coaching cycle.

Over time, I adapted Barkley’s method of instructional coaching so I can work with teachers across various subjects and disciplines as well as administrators who desire to determine needs and a path forward for teaching and learning at their school.

It begins with having teachers or leaders determine an overall goal they wish to achieve. Most of the time, these goals at first are very broad at the beginning (e.g. increase student achievement, lower behavior problems, increase teacher agency). I’ve learned to take a deductive approach with this goal setting and narrow their focus by asking questions to develop a framework that will allow for visualization of their goals.

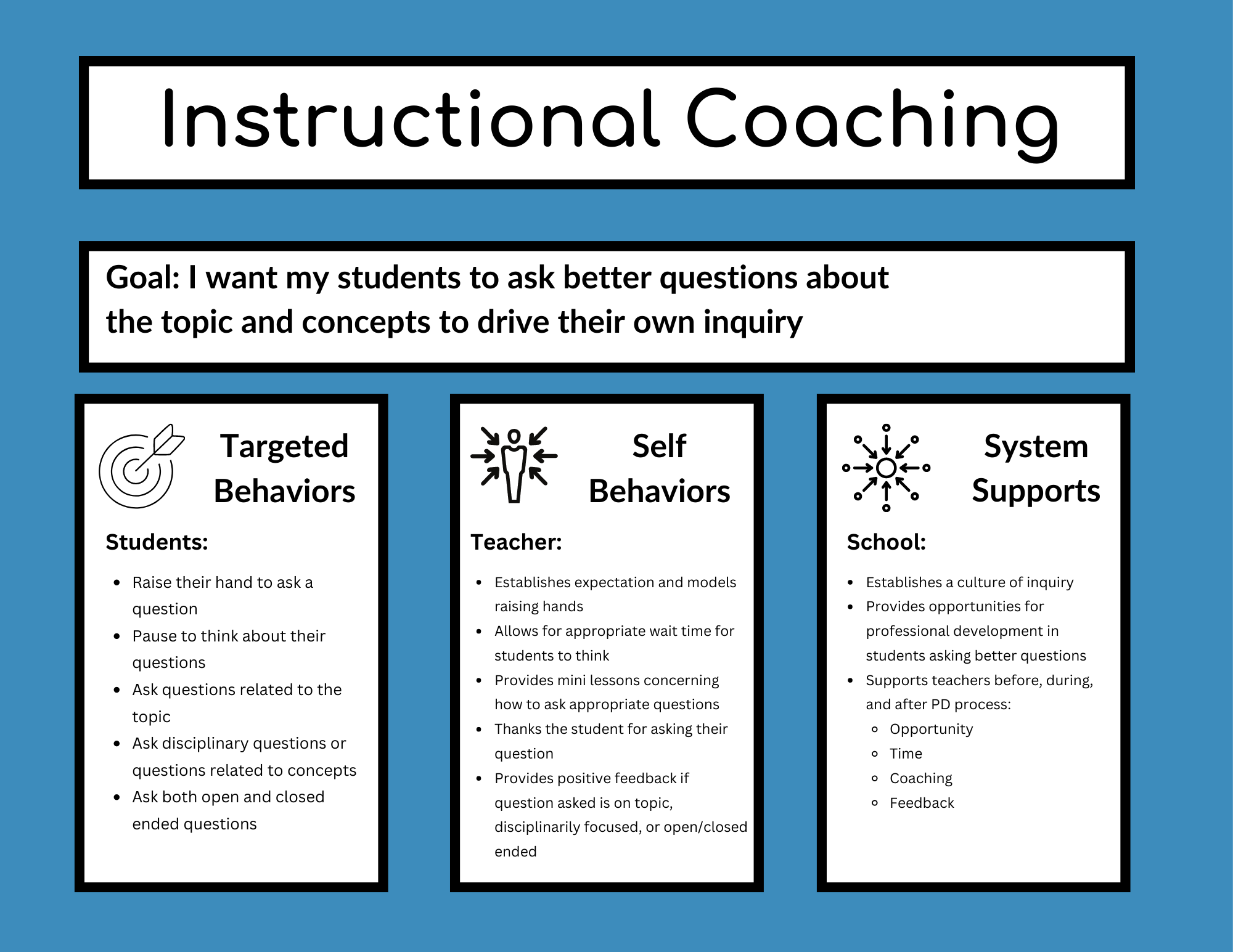

My first question is always, “What does success look like/sound like if you were to accomplish your goal?” This will draw out specific observable targeted behaviors where feedback can be provided. The following chart below provides an example I used with a 3rd grade teacher once concerning her goal of getting her students to ask better questions in the classroom.

After discussing her goals and concerns, I asked: “If students were asking good questions, what would this look like and sound like?” After thinking, the teacher was able to identify five observable targeted behaviors that students would be doing during the lesson to ask good questions. But how would we know? What data can be collected? How would it be collected?

I asked the teacher if it would help if I observed a lesson and simply provided her with data she needed concerning these behaviors. This model of instructional coaching provides an opportunity for the teacher to take the lead in their wants and needs without having the coach to appear to be a “fixer.” When she agreed, I told her that I would come into the classroom and write down every single question the students asked during that time period. Then, she would have the necessary data to determine any next steps.

Early the next week, I observed a lesson and wrote down all of the question students asked during a Read Aloud. True to form, the third grade questions ranged from “Can I go to the restroom?” to “When is lunch?” to “Why is that dog sitting like that?” There was a mixture of open and closed ended questions and a few focused disciplinary questions the teacher was hoping for from the students as well.

Before I left, I thanked the teacher and left the list of questions on her desk for her to review. I followed up with her the next day asking if she wanted to debrief, and she was excited to share her thoughts as to what she might need to do to improve. What I learned most from Steve Barkley was the idea of peeling back the layers of goal setting. In order for her students behavior (asking questions) to change, the teacher needed to also reflect on and change her actions as well. We took out the same list and I guided her through uncovering what behaviors she must exhibit for her to yield the behaviors she wanted in her students. Again, all of these were observable behaviors that if needed, could have feedback provided for her through observation or other forms of data collection.

Once we created the behaviors that was necessary for her to enable her students the opportunity to ask better questions, she quickly realized areas of her own growth that was needed to create the change she desired in her students.

Sometimes, schools do not have the necessary structures for teachers’ goals to be successful. If a teacher is wanting to dive deeper into student inquiry, not all schools have developed a culture nor expectations of student inquiry throughout the school. If a teacher simply doesn’t have the knowledge, skills, and tools for how to have her students ask better questions, the appropriate profession development must be provided to enable the teacher to accomplish their goals.

We then brainstormed what changes to the “system” might be needed for her to be successful. These are specific needs she can discuss with her administration concerning how they can support her professional growth and increase student achievement in asking better questions. While these behaviors can take some time to implement, it is an important though process that also takes time to uncover what is truly needed.

An instructional coach can help with this process, and I continue to try my best to refine my skills in coaching for teachers and leaders.

A Guaranteed and Viable Curriculum

It all begins with an idea.

It all begins with an idea. Maybe you want to launch a business. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into something more. Or maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sound like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest. If you read the words back and don’t hear your own voice in your head, that’s a good sign you still have more work to do.

Be clear, be confident and don’t overthink it. The beauty of your story is that it’s going to continue to evolve and your site can evolve with it. Your goal should be to make it feel right for right now. Later will take care of itself. It always does.

Meeting vs Exemplifying a Standard

It all begins with an idea.

Common language plays an important part in a grading system. No matter what symbol or number is applied to a certain level of proficiency, expectation, or standard, as long as it is clearly communicated among teachers, students, and parents, it has more of a chance to maintain its integrity within the system.

Several years ago I was a teacher at a middle school that moved to a 4 point grading scale where by a 1 would represent "below standard”, a 2 "approaching standard”, a 3 as "meeting standard", and 4 as “exemplary.” Guskey provides a great rationale for using exemplary instead of "exceeds" in this article.

While both parents and students were a bit confused about the new system, the language used when students discussed their feedback was immediate. Instead of saying, “I got an A” or “I got a 90%,” students were now saying that they “met the standard” or were “approaching the standard.” As long as teachers were clearly explaining what the "standard" actually was, this terminology positively changed students' thoughts on their feedback. As anyone who has ever gone through this process, this phase is crucial for teachers to then determine the criteria for what below, approaching, meeting, and exemplary will actually be for each assessment.

While some common rubrics for assessments developed rather easily in math and language arts, some subjects faced more of a difficult challenge. Nonetheless, teachers soon realized that if they were to give a student a “3” according to the standard, then the criteria must be clearly communicated not only after the assessment but before. In general, teachers found it easy to determine evidence of the proficiency of the standard. Likewise, it was easy for them to see what evidence would be below or approaching the standard. More difficult, however, was how a student could become exemplary. While it would look different at various subjects, “exemplifying” a standard deemed to be tricky for some teachers.

I often tell this story when trying to explain how these two levels can be described. We once traveled with a group of students on a study trip to eastern Europe and always had the students count off when we reconvened at certain locations. Students were given a number, and they counted up to 25 so we could quickly get a count of who was or was not there. Luckily, all students were there every single time, but our numbering system was efficient for the chaperones.

Students initially struggled with the numbering. They wouldn’t listen, would be distracted by people walking by, would forget their number, or simply zone out and not answer. Over time, I began to give them a 4 point “grading” each time they counted off. After a while of getting nothing but 2’s or perhaps even a generous 2.5, students finally asked, “How do we even get a 3? Or even 4?”

We quickly rattled off the criteria for a 3:

When asked, students must begin counting one by one with their number until we clearly heard all numbers through 25.

We gave them a rough estimate of about 1 number per second; so in general, they should be finished under 30 seconds each time. However, it was more important to be clear and accurate in the counting so everyone was accounted. If they stumbled, skipped numbers, or forgot them, it would be either a 1 or a 2 based on the severity.

This became a fun way for them to try and improve their numbering through the week. But what about the 4? If meeting the standard in counting off is simply all students being clearly heard counting off to 25, how could this be “exemplified?” Exemplifying a standard suggests that students are not only meeting the criteria of the standard but applying it in new novel or authentic ways. So, because we were on the bus to another tourist location, we put our heads together and came up with this list:

Begin the numbering without being asked (independence)

Count in another language or even sign language (fluency)

Count off backwards (flexibility)

Explain the reason for counting off (reasoning)

Determine what would happen if one of the numbers was missing (problem solving)

Of important note was that no one mentioned for the students to count faster or louder. Because our directions indicated that students only need to be clear and accurate, there was no need to necessarily be faster or louder.

So, how did they do? While we never got around to their ability to do any of the “4” criteria, they were able to become consistent in earning a “3” each time the last three days of the trip. Like many standards, sometimes students simply just need more time or clarity to finish the task.

The transfer of these "exemplary" skills will become the standard and a shift I believe in education over the next 20 years. We already see these words embedded of the new curriculum standards and frameworks (CCSS mathematical practices, NGSS practices, C3 dimensions, etc.). What is left is for teachers to provide students with opportunities within their assessments and evaluations to apply these skills in an authentic situation.

Just as we were able to accomplish on the bus that day, conversation and collaboration become key factors as teachers and schools try to determine what it means to exemplify a standard.